One of his biographers Patrick Geddes wrote: “The life story of Jagadis Chandra Bose is worthy of close and ardent consideration by all young Indians whose purpose is shaping itself towards the service of science or another high course of the intelligence or social spirit. It is possible that looking upon the triumph of the end and knowing nothing of the long uphill road, the slow, costly attainment of ends, they may think that a fine laboratory or another material endowment the antecedent condition of achievement in intellectual creation. The truth indeed is far otherwise. The countless obstacles which had to be surmounted only called forth in Bose all the endurance…In contemplating the great career of his countryman, the young Indian will be stimulated to put brain and hand to fine tasks, nothing fearing.”

Writing in The Life and Work of Sir Jagadis C. Bose, Geddes quotes Late Mrs. A.M. Bose, eldest sister of J.C. Bose, “At our country house, Fairy Hall at Dumdum, outside Calcutta (now Kolkata) I watched Jagadis’s passion towards the peculiar movements of leaflets of Biophytum, which led to his discovery of multiple responses, and its continuity with the automatic response of the Telegraph-plant”.

Bose did pioneering research, first in physics and then in plant physiology. He was the first to produce and study the properties of millimetres-length radio waves and perfected the method of transmission and reception of electromagnetic waves. Additionally, he showed, semiconductor rectifiers could detect radio waves. His galena receiver of lead sulphide photo-conducting device was amongst the earliest. W.H. Brattain (1902-1987), the Nobel Laureate American physicist who co-invented the transistor, credits Bose with the first use of semi-conducting crystals to detect radio waves. According to Nevill Mott (1905-1996), the British physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1977, “He (Bose) had anticipated the existence of p-type and n-type semiconductors.”

Bose was a pioneer in experimental science in India; yet much against the philosophy of patenting. His American friend persuaded him to file a patent application for his galena receiver. The patent (US patent no. 755,840) was granted on 29 March 1904 after nearly two years from the date of application. Bose refused to accept his rights and the patent lapsed.

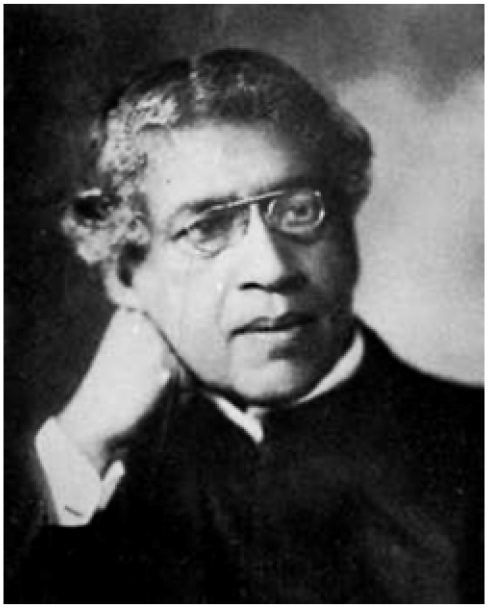

Jagadish Chandra Bose was born in Mymensingh (now in Bangladesh). His father Bhagwan Chandra Bose, a civil servant in the British Raj, was deeply interested in the welfare of his fellow citizens. He was particularly interested in improving the living conditions of rural people and always thought of new schemes for their benefit. Bose had his early education in a local vernacular or a Bengali-medium school, a pathshala, founded by his father in Faridpur. His father had the option of sending him to a local English school. He, however, wanted his son to learn his mother tongue well, know his culture before he learned English and imbibed foreign culture. In this pathshala, children of peasants, fishermen and workers were his classmates. In fact, one of the students studying with him was the son of his domestic servant! In their midst, Bose imbibed an abiding love for animals, birds, and plants, as many of his later writings bear testimony to this. He also developed a love of equality and brotherhood, and he was free from caste, class, and religious prejudices. His father used to take his young son for evening strolls in the neighbouring areas and make him familiar with the natural objects around them. He used to encourage young Bose to ask questions. There used to be occasions when he could not answer the question and in such situations, he prompted him to look for answers by himself and even as he would grow up. This developed a spirit of asking questions in young Bose. In his childhood, Bose was inspired through folk plays to read the Ramayana and Mahabharata. He was deeply influenced particularly by Karna from Mahabharata.

In 1869, Bose proceeded to Calcutta. After three months at the Hare School, he joined St. Xavier’s College, that included a secondary school; founded by Belgian Jesuits in 1860. Bose came in contact with Father Eugene Lafont (1837-1908), who helped established the tradition of modern science in Kolkata. Father Lafont’s laid a lot of emphasis on experimentation. Bose was highly influenced by this approach of Father Lafont. In 1879, Bose passed the degree (BA) examination in Physical Science of the Calcutta University. At that Bose was not clear about his career path. He had the option of following his father’s example to join the Indian Civil Service. However, his father did not want his son to become a civil servant and in fact serve common people.

It was finally decided that Bose would study medicine in an English university. So finally Bose went to England in 1880. His mother had to sell off her jewellery to send him to England. But Bose had to abandon his plan to study medicine as he fell ill, due to odours in the dissecting rooms. In January 1882, Bose left London for Cambridge to join the Christ College and study natural science. Among his teachers at Cambridge was the famous scientist Lord Rayleigh (1842-1919) with whom Bose struck a life-long friendship. In 1884, Bose passed the Natural Sciences Tripos; the same year he obtained the Bachelor of Science degree from the University of London. On returning to India in 1885, he joined the Presidency College in Kolkata and served as the first Indian Professor of Physics. His appointment was initially strongly opposed by Sir Alfred Croft, Director of Public Instruction of Bengal and Charles R. Tawney, the Principal of the Presidency College. Despite these, Bose finally secured appointment through the intervention of Lord Ripon, then Viceroy of British India.

British officials of that period were biased against Indians, that the latter cannot handle high posts in educational service. The Imperial Educational Service was therefore beyond their reach despite high qualifications. Against this back drop Bose was taken only on a temporary basis at half the pay. Bose protested and asked for salary; an Englishman was entitled for. He refused to accept the half salary when his plea was not heard. He continued teaching without pay for three years. This was even at a time when his father was deep in debts. Finally, the Director of Public Instruction and the Principal of the Presidency College took note of Bose’s skill in teaching and his tenacity. This helped Bose secure a permanent appointment with retrospective effect. He used the money he received to pay his father’s debts off.

In 1894, Bose decided to pursue scientific research in real earnest, and not be confined to teaching alone. He conducted research in a small room at the Presidency College. He received help from an untrained tinsmith to devise and construct new apparatuses for his researches on electric waves. He studied properties of electric waves; inspired by Oliver Lodge’s book Heinrich Hertz and His Successors. Bose devised and fabricated a new type of radiator to generate radio waves and highly sensitive ‘coherer’ or detector to receive radio waves. This coherer was more compact, efficient and effective than the ones used in Europe at that time. Using his improved equipment he demonstrated such properties of radio waves as reflection, absorption, interference, double reflection and polarisation. He also demonstrated micro waves of 5 to 10 millimetres. These waves are used in radars, ground telecommunication, remote sensing, and microwave ovens.

At a public demonstration in the Town Hall, Kolkata in 1895 he transmitted electric waves through three walls and activated a receiver that caused a bell to ring; a pistol fire; and a small heap of gunpowder explode. Among those present to witness this great event was Sir Alexander Mackenzie, the then Lieutenant Governor of Bengal.

His first research paper before the Asiatic Society of Bengal in May 1895 was titled, “On the Polarisation of Electric Rays by Double Refracting Crystals”. His other paper that year was “On the Determination of the Index of Refraction of Sulphur for the Electric Ray”. This was communicated by Lord Rayleigh to the Royal Society of London. The paper was read before the Royal Society in December 1895 and accepted for publication in the Society’s proceedings in January 1896. Bose’s three articles were published in the Electrician, Friday 27 December 1895. In those days Electrician was amongst the most prominent periodicals devoted to electrical matters. The University of London awarded Bose the Doctor of Science (DSc) degree without any examination. Lord Kelvin congratulated Bose stating he was “literally filled with wonder and admiration…for his success in the difficult and novel experimental problem.”

Bose’s success in his researches and appreciation by leading scientists in England and other European countries prompted the Education Department to send him to England on deputation. On reaching England, Bose first presented a lecture-cum-demonstration on his new findings at the meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. This was at Liverpool. Scientists at the meeting were highly impressed by his presentation. J.J. Thomson, Oliver Lodge, and Lord Kelvin were amongst them. Bose was invited by the Royal Institution to deliver a Friday Evening Discourse on 29 January 1897; a matter of great honour. The lecture was not only praised but was considered for publication in the Transactions of the Royal Society. The Government of India extended his deputation. Bose’s fame spread to France and Germany. He was invited by the Physical Society of Paris and leading physicists of Berlin to deliberate on his results.

After pioneering work in physics, Bose focussed on plant physiology. He demonstrated electric responses produced by plants in response to mechanical stimuli, application of heat, electric shock, chemicals, and poisons. He tried to demonstrate a similar electric response to simulation in certain inorganic systems and the physical basis of memory. Bose invented several novel and highly sensitive instruments for his investigations. Among these, the most important one was the crescograph–an instrument for measuring the growth of a plant. It could record growth as minute as 1/100,000th of an inch (0.00003 cm) per second. In all his investigations, Bose offered original interpretations. His findings subsequently influenced knowledge systems in biophysics, chronobiology, cybernetics, medicine and agriculture.

Bose retired from educational service in 1915. After his retirement, he established a research institute–the Bose Institute in Kolkata. The foundation ceremony of the Institute took place on 23 November 1917. Bose collected nearly Rs.11 lakh for its endowment; with help from Rabindranath Tagore. Bose became the Lifetime Director of the Institute. In his inaugural speech, he said: “I dedicate to-day this institute–not merely a laboratory but a temple…The advance of science is the principal object of this Institute and also the diffusion of knowledge…I have sought permanently to associate the advancement of knowledge with the widest possible civic and public diffusion of it; and this without any academic limitations, henceforth to all races and languages, to both men and women alike, and for all time coming.”

Bose was a close friend of Rabindranath Tagore. He received significant emotional support from him in times of difficulty. Before seriously launching into scientific investigations in 1894, Bose visited and photographed historic places of scenic beauty. He documented some of his experiences in vivid Bengali prose.; published later as Abyakta (The Inexpressible). Bose was conferred Knighthood by the British Government in 1917. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of London in 1920.