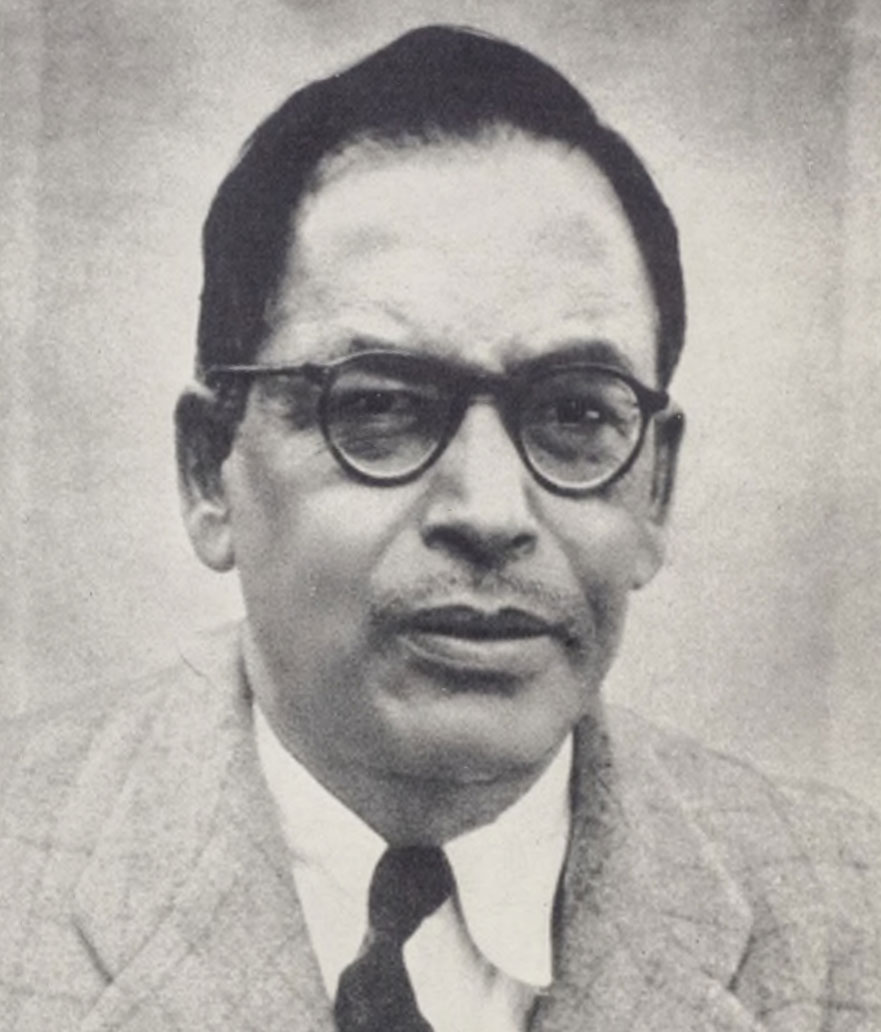

Arthur Stanley Eddington, the British astrophysicist, and mathematician, while writing on stars in the fourteenth edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, described Saha’s theory of thermal ionisation as one of the twelve most important landmarks in the history of astronomy since the first variable star (Mira Ceti) was discovered by David Fabricius in 1596. Saha became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1927 at the age of 34. “MeghnadSaha’s place in the history of astrophysics and the in the history of modern science in India is unique,” wrote the Nobel Laureate astrophysicist Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar.

MeghnadSaha was born on 16 October 1893 in the village of Seoratali in the Dacca district (now Dhaka in Bangladesh) of undivided India. He was the fifth child of his parents, Jagannath Saha and Bhubaneswari Devi. His father was the owner of a petty grocery shop, and somehow he was able to make ends meet and maintain his big family of eight children. Given their social and economic background, his parents had neither the means nor the inclination to educate their children beyond the primary level. So, after the completion of his primary education, there was no certainty that young Saha’s education would continue. There was no middle school near his village. The nearest middle school was at Simulia, which was 10 km away from his village. His parents could hardly afford the expenses, and they would have preferred to have him work in the family’s grocery shop.

However, his elder brother Jainath, who was working in a jute company, came to Saha’s rescue by locating a sponsor in Ananta Kumar Das, a local doctor. The kind-hearted doctor agreed to provide free boarding and lodging in his house provided Saha washed his plates (a condition that reflected the prevailing rigid caste system) and attended to minor household works including the taking care of the cow. Saha readily accepted all the conditions. He completed his middle school by topping the list in the entire district, and he also secured a scholarship of Rs.4 per month. In 1905, Saha went to Dhaka and joined the Collegiate School.

There were widespread political disturbances in Bengal in 1905, the year in which Lord Curzon, the then Viceroy of India under the British Rule, had decided to partition Bengal. Saha, like many others, was affected by this political upheaval. He, along with some other students, was rusticated from the Collegiate School because of their participation in the demonstration against the visit of the Bengal Governor, Sir Bampfylde Fuller, to the school. Besides being rusticated, Saha was also deprived of his scholarship. Fortunately, a private school named KishoriLal Jubilee School accepted Saha with a free studentship and a stipend.

In school, Saha’s favourite subject was mathematics. He also liked history. He was particularly fond of reading Todd’s Rajasthan. Among his favourite books were Rabindranath Tagore’s Katha O Kahini, which glorifies the values of the Rajput and Maratha warriors, and MadhusudanDutt’s epic poem Megnadhbadh. During the school days, he also attended the free Bible classes conducted by the Dhaka Baptist Mission. He stood first in one of the competitive examinations on Bible conducted by the Mission and received a cash prize.

In 1909, Saha passed the Collegiate Entrance examination, standing first amongst all the candidates from the erstwhile East Bengal. After passing the Intermediate examination of Calcutta University in 1911 from the Dhaka College, Dhaka, Saha joined Presidency College. Among his classmates in Presidency College was SatyendraNath Bose. Prasanta Chandra Mohalanobis, the founder of the Indian Statistical Institute, was his senior by a year. His teachers included Prafulla Chandra Ray in chemistry ad Jagadis Chandra Bose in physics. Saha passed his BSc Examination with Honours in Mathematics in 1913 and MSc (Applied mathematics) examination in 1915. Saha stood second in order of merit in both the examinations. The first positions in both cases went to S.N. Bose.

Saha was appointed Lecturer in the Department of Applied Mathematics in 1916. However, after one year both Saha and S.N. Bose, who had also joined the Department of Applied Mathematics, got themselves transferred to the Physics Department. In the Physics Department Saha started giving lectures to the post-graduate classes on topics like hydrostatics, spectroscopy, and thermodynamics. For teaching physics to the postgraduate classes, Saha had first to learn it himself, as he had studied physics only in undergraduate classes. Besides teaching, Saha also started doing research. It was not an easy task. In those days there was no laboratory in the Department of Physics of the University College of Science. Saha had no guide for supervising his research work. He totally depended on knowledge acquired from his studies. Working under the most adverse circumstances, Saha forwarded his theory of thermal ionisation.

He submitted his thesis on radiation pressure and electromagnetic radiation for the degree of Doctor of Science of Calcutta University in 1918. He was awarded the degree in 1919. The same year he was awarded the PremchandRoychand Scholarship for his dissertation on the ‘Harvard Classification of Stellar Spectra’. The scholarship enabled Saha to spend about two years in Europe. He first went to London where he spent about five months in the laboratory of Alfred Fowler (1868-1940). From London, he moved to Berlin where he worked in Walther Nernst’s Laboratory. In November 1921, Saha returned to India and joined the University of Calcutta as Khaira Professor of Physics, a new chair created from the endowment of Kumar Guruprasad Singh of Khaira.

In 1923, Saha went to the Allahabad University to join the Physics Department. Saha is credited with making the Physics Department of the Allahabad University one of the most active centres of research in the country, particularly in the field of spectroscopy. He also initiated and organised research in statistical mechanics, atomic and molecular spectroscopy, the electron affinity of electronegative elements, high-temperature dissociation of molecules, propagation of radio waves in the ionosphere, and physics of the upper atmosphere. The Department attracted students from all over the country. At Allahabad, Saha wrote his famous textbook, which was first published under the title of A Textbook of Heat. The book was jointly written with B.N. Srivastava. A concise version was published for science graduates. It was titled Junior Textbook of Heat. Later Saha wrote another book (jointly with N.K. Saha) titled Treatise on Modern Physics.

Saha returned to Calcutta University in July 1938. He became the Palit Professor and Head of the Department of Physics. He remodelled the MSc syllabus in physics of Calcutta University. It was Saha who first started teaching and training in nuclear physics in the country. He introduced a general paper and a special paper in nuclear physics in 1940; soon after the phenomenon of the nuclear fission was discovered by Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann. Saha played the lead role in building the first cyclotron in the country.

Saha, jointly with S.N. Bose, prepared an English translation of Einstein’s papers on the theory of relativity and published them in the form of a book. This translation of Einstein’s work on the theory of relativity form German into English happened to be the first on record. Thus Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar wrote: “…In 1919, only three years after the founding of the general theory of relativity, Saha and S.N. Bose should have taken the time and the effort to translate and publish Einstein’s papers, which have since become epochal. At a celebration of the Einstein Centennial at Princeton University, three years ago, reference was made to a Japanese translation of Einstein’s papers as the first on record and I was glad that I was able to correct the impression. A Xerox copy of the Saha- Bose translation is now in the Einstein Archives at Princeton.”

Saha was an active member of the National Planning Committee constituted by the Indian National Congress in 1938 with Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru as its Chairman. In fact, it was Saha who had persuaded NetajiSubhash Chandra Bose, then President of the Indian National Congress, to set up the National Planning Committee. He was the Chairman of the Indian Calendar Reform Committee constituted by the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research in 1952. He was an elected Independent Member of the Indian Parliament. He advocated large-scale industrialisation for social development.

Saha was a great institution builder. In 1930, he founded the UP Academy of Sciences at Allahabad, which was later renamed as the National Academy of Sciences, India. The Academy was formally inaugurated on 1 March 1932 and Saha was its first President. In 1933, Saha established the Indian Physical Society at Kolkata. The Society published the Indian Journal of Physics. Eminent scientists like C.V. Raman and K.S. Krishnan regularly contributed important papers to the Indian Journal of Physics. With Saha’s initiative, the National Institute of Sciences of India was established in Kolkata in 1935, which was moved to New Delhi in 1946. In 1970, it was renamed as the Indian National Science Academy (INSA).

Saha was closely associated with the planning and establishment of the Central Glass and Ceramic Research Institute, a constituent laboratory of the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research at Kolkata. Saha was elected the Honorary Secretary of the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science, and he was its President during 1946-050. After his retirement from Calcutta University in 1953, Saha became the full-time Director of the laboratories of the Association, a post he held until his death. Under his leadership, there was a large-scale expansion of the activities of the Association. Saha played a significant role in the establishment of the Departments of Radio Physics and Electronics and Applied Physics of the Calcutta University. In 1950, Saha founded the Institute of Nuclear Physics (later renamed as the Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics). The foundation stone of the Institute was laid by Dr. Shyama Prasad Mookerjee – the then Civil Supplies Minister of the Government of India. The Institute, which was formally inaugurated by Iren Joliot- Curie on 11 January 1950, was originally situated on the campus of Calcutta University. Among those who attended the inauguration were Robert Robinson and J.D. Bernal.

Saha founded the Indian Science News Association in Kolkata in 1935. Its main objective was to disseminate science amongst the public. The Association started publishing a journal called Science and Culture. Saha himself wrote more than 200 articles in the journal on a wide range of topics which included: organisation of scientific and industrial research, atomic energy and its industrial research, river valley development projects, planning the national economy, educational reforms and modification of Indian calendar.

Renowned physicist and science populariser ShantimayaChatterjee, a colleague of MeghnadSaha, wrote, “Whenever Saha wanted to write or express his ideas on any topic he would work very hard to prepare for it. He would try to understand the crux of the problem, study all the available information on the subject and then by his analysis would try to find a solution for it. I had the opportunity to go to Asiatic Society, National Library, Victoria Memorial and other libraries of Calcutta with Professor Saha. I saw how perfectly and meticulously he would prepare his report and documents after a deep study. When he became a member of parliament, he took full advantage of apartment Library, and he used to speak very highly about it.”

Saha died suddenly due to a massive heart attack on his way to the office of the Planning Commission in New Delhi on 16 February 1956. As D.S. Kothari, a student of Saha and founder of defence research in India, wrote: “The life of Saha was in a sense an integral part of the growth of scientific research and progress in India and the effect of his views and personality would be felt for a long time to come in almost every aspect of scientific activity in the country. His dedication to science, his foresightedness and utter disregard of personal comforts in the pursuit of his chosen vocation will long remain an inspiration and example.”