Koch was not able to work out the process behind the typical symptoms of the disease – the uncontrolled ‘rice-water’ diarrhoea. Mistaking the cause for effect, Koch reported that systemic toxinosis ( a disease caused by the bacterial toxin alone, not necessarily involving bacterial infection) and multi-organ failure led to severe dehydrating diarrhoea. As a result, while vaccines and drugs were developed for other microbial pathogens, the only measures put forward to prevent the spread of cholera were better sanitation and other public health measures. Sambhu Nath De used a novel technique to produce the symptoms of cholera artificially in rabbit intestine. He was able to demonstrate that cholera was caused by a toxin produced by Vibrio cholerae and not the bacteria itself. This finding opened up a dynamic new era of cholera research leading to oral vaccines against the disease. It is De’s work that transformed cholera from being a dreaded killer to a disease that could be tamed. His findings were published in the British science journal Nature in 1959. Eugene Garfield concluded that De’s 1959 paper in Nature, “while initially unrecognised, today is considered a milestone in the history of cholera research”.

His scientific eminence can be clearly gauged from the comments of his PhD guide Professor Roy Cameron, Head of the Department of Morbid Anatomy in the teaching hospital of University College, London. Cameron, one of the world’s leading pathologists, said: “There is no doubt about it – he is one of the most outstanding of young men I have had through my hands and am prepared to believe that he is probably the best of the experimental pathologists in India… I am confirmed in my belief by other people’s opinion.”

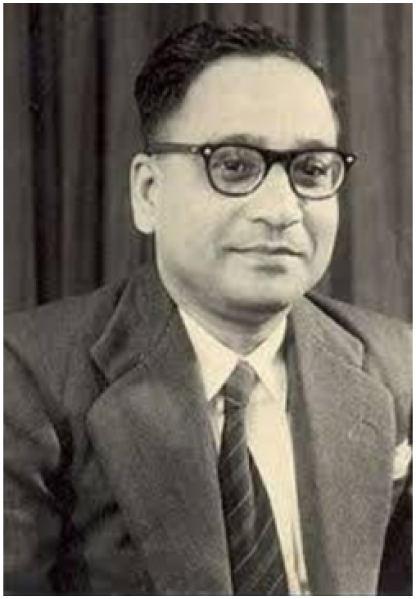

Sambhu Nath De had humble beginnings. He was born on 1 February 1915 in a small village, called Garibati, on the west bank of river Hooghly, about 40 km north of Calcutta (now Kolkata). After his initial schooling at the local high school, followed by a stint in the Hooghly Mohsin College, De received a scholarship in his inter-science examination and was admitted to the Calcutta Medical College. Here, in 1942, he also took up the job of a demonstrator in pathology and while working under Prof. B.P. Trivedi and published a few papers jointly with him. In 1947, Sambhu Nath went to England and joined the University College Hospital Medical School in London to work under Prof. G.R. Cameron, FRS (later Sir Roy Cameron) as a PhD student. He was awarded the PhD degree from the London University in 1949.

De returned to Calcutta soon after and joined the Calcutta Medical College, before taking up the Chair of Pathology at the Nilratan Sircar Medical College. High-calibre research in the UK had transformed him, and he became truly and completely focussed on his research work on the pathogenesis of cholera. At the Nilratan Sircar Medical College, Sambhu Nath began studying the damaging effects of cholera on kidneys. The Medical College provided him easy access to numerous cholera cases admitted to the attached hospital for treatment. He published several research papers on this topic between 1950 and 1955.

De had his moments of frustration, though. He could not purify the toxin or stabilise his collection of the strain. He wrote about this frustration to W.E. van Heyningen, who too worked on bacterial toxins that “workers in developed countries cannot imagine how difficult it is to carry out and continue research work without willing personnel and without equipment in an undergraduate teaching department in a country like ours”. However, these challenges did not deter his progress.

His novel technique for discovering cholera enterotoxin with the rabbit ileal loop has been widely recognised. (Ileal loop involves use of a segment of the ileum (part of the small intestine) for the diversion of urinary flow from the ureters. Ileal loop urinary diversion creates an opening on the abdominal wall that drains urine into a bag.) John P. Craig, a Professor at the State University of New York Health Center, New York, USA says about De’s model: “Many of us who have worked in this area took for granted the discovery of this seemingly simple model system. But, looking back, it seems the world needed the fertile mind of an investigator whose natural scientific instincts forced him to shun the conventional approaches…No matter how simple it may seem, his truly creative and novel piece of work started a chain of events which, in turn, forever altered our concepts surrounding the pathogenesis of secretory diarrhoea.”

De and his co-workers also carried out extensive studies on diarrhoea produced by the common gut bacteria Escherichia coli, especially in infants. Using the rabbit loop experiment they were able to show that in both cholera and E. coli diarrhoea, the symptoms were produced by similar mechanisms.

Sambhu Nath De did not enjoy large gatherings, seminars and conferences. He maintained a distance from centres of power. No wonder, De retired from Calcutta Medical College in 1973, almost unknown despite his path-breaking contribution in cholera research. He did not receive any recognition; either a fellowship of an Academy, awards or honours. The Coates Medal awarded by Calcutta University in 1956 for outstanding research was the only one he secured. Prof. Padmanabhan Balaram of the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru pointed out in an editorial in Current Science, “De died in 1985, unhonoured and unsung in India’s scientific circles. That De received no major award in India during his lifetime and our Academies did not see it fit to elect him to their Fellowships must rank as one of the most glaring omissions of our time.”

De retired in 1973 from the Calcutta Medical College at the age of 58 and showed no interest in higher positions. A sort of recognition came in 1978 when he was invited to the 43rd Nobel Symposium on Cholera and Related Diarrhoeas held in Stockholm. At the end of his presentation to the Nobel Symposium, S.N. De said: “Chairman and Friends, before I conclude I wish to make a few personal remarks. I have been dead since the early 1960s, I have been exhumed by the Nobel Symposium Committee and these two days with you make me feel that I am coming to life again.”

De died in Calcutta on 15 April 1985. Paying tribute to him in a commemorative issue of Current Science, Nobel laureate Joshua Lederberg wrote, “Our appreciation for De must extend beyond the humanitarian consequences of his discovery….he is also an exemplar and inspiration for a boldness of challenge to the established wisdom, a style of thought that should be more aggressively taught by example as well as precept.” There can be no better tribute for De, a modest scientist who spent his life grappling with a problem that had been tormenting humanity for long. He died largely unsung and did not receive his due honours.