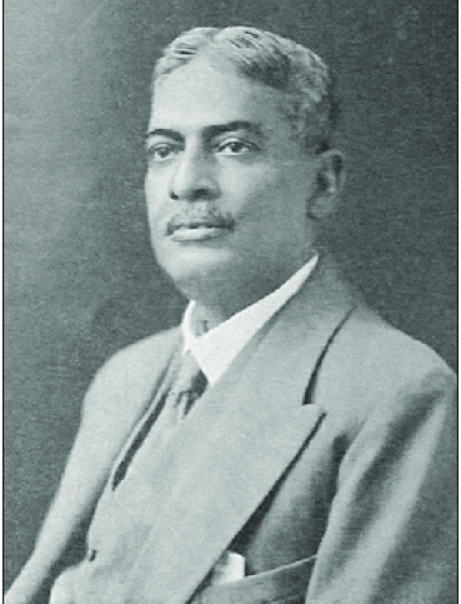

Upendranath Brahmachari was born in Jamalpur, Monghyr (Munger) district, Bihar, to Dr.Nilmony Brahmachari and Saurabh Sundari Devi. The family had its ancestral roots in Sardanga village in West Bengal. He received his early education at the Eastern Railways Boys’ High School, Jamalpur. After passing his entrance examination, he joined the Hooghly Mohsin College, from where he secured his BA degree in 1893. He graduated with honours in mathematics and chemistry standing first in the order of merit in mathematics. He was awarded the Thwaytes Medal for Mathematics.

A glimpse of his intellect can be gleaned from the fact that he took up the simultaneous study of chemistry at Presidency College, Calcutta (now Kolkata) with the study of medicine at the Medical College. He received his master’s degree in chemistry in 1894. Subsequently, in 1900 he obtained top rank in the MB examination, standing first in Medicine and Surgery. He received the McLeod and Goodeve Medal for this feat. He earned his MD in 1902 and PhD in 1904, from the University of Calcutta. His thesis titled Studies in Haemolysis is still considered an important piece of research on the physiological and physiochemical properties of red blood cells.

While pursuing higher education, he joined service in 1899 with the Provincial Medical Services, Dhaka. In 1901 he joined Dacca (Dhaka) Medical School as ‘Teacher of Physiology and Materia Medica and Physician’ −a post he graced for four years. A year after securing his doctoral degree, he joined the Campbell Medical School, Calcutta (now Nil Ratan Sircar Medical College, Kolkata) as ‘Teacher and First Physician’. In 1923 he joined the Medical College Hospital, Kolkata, as Additional Physician−a post from which he retired in 1927. Subsequently, he joined the Carmichael Medical College as Professor of Tropical Diseases. He also served the National Medical Institute as In-charge, Tropical Disease Ward and was Head of the Department of Biochemistry, and Honorary Professor of Biochemistry at the University College of Science, Kolkata. He was also the Chairman of the Blood Transfusion Service of Bengal and played an important role in establishing the world’s second blood bank in Kolkata in 1939.

Between 1915 and 1921, Brahmachari carried out many experiments in a small laboratory attached to the Campbell Medical School. His laboratory was a small, ill- equipped room lacking even such basic facilities as a gas burner, water tap or an electric bulb. Undeterred, he carried out his research by the light of a lantern. In 1919 he prepared an arsenic-containing unstable acid called stibanilic acid and various salts. The next year he made urea stibamine by heating stibanilic acid with urea. It was the world’s first pentavalent antimonial drug designed to treat kala-azar. Looking back on the miserable conditions of his laboratory, he later said, “To me, it will ever remain a place of pilgrimage where the first light of urea stibamine dawned upon my mind.” This attitude can only be attained by a mind so truly immersed in the subject of study so as to transcend all material limitations.

Urea stibamine was the first organic antimonial compound to achieve wide acceptance as a treatment for human leishmaniasis. Brahmachari tested it on the patients at Campbell Medical School with “gratifying results.” In October 1922 he published his results in the Indian Journal of Medical Research, and the world began to take notice. A much larger number of patients now began to receive this new medicine in different wards of the Calcutta Medical College and Hospital. By 1923 it was evident that this once- fatal infection was fully cured, three weeks after an injection of 1.5 gm of urea stibamine. Brahmachari shared this medicine with doctors at the Pasteur Institute, Shillong and there too, the results were successfully replicated. Subsequently, there was hardly any hospital in India that did not receive urea stibamine free of charge. By 1925, the mortality rate from kala-azar had plunged to 10 per cent from 95 per cent, and it dipped to 7 per cent by 1936. The effect was particularly dramatic in the Gangetic plains and Brahmaputra Valley, the epicentre of kala-azar in those days. Greece, France and China too reported success.

Brahmachari was a scientist with far-ranging interests, but it was the generous spirit and empathy that characterised the person he was. Few know that he took note of the fact that urea in combination with certain drugs reduces the pain on injection. The process of making urea stibamine was never patented. This shows the magnanimity of Brahmachari, for urea stibamine was a brand new weapon in a medicinal quiver that held few specific medicines apart from quinine for malaria, arsenic for syphilis and digitalis for heart conditions and patenting it could have earned large amounts of money for him.

Brahmachari married Nani Bala Devi in 1898. They had two sons Phanindra Nath and Nirmal Kumar. Around 1924, Brahmachari established a research institute at his residence which was later converted into a Partnership concern with his sons. Unfortunately, this institute has not stood the test of time. Brahmachari is celebrated for his work on kala-azar. He also worked on malaria, blackwater fever, cerebrospinal meningitis, diabetes, filariasis, old Burdwan fever, influenza, leprosy, and syphilis. He was the first to identify the rare quartan fever (a type of malaria fever that recurs every 72 hours) in Kolkata and Dacca. He also identified a cutaneous leishmaniasis that occurs in patients who have recovered from kala-azar. This is christened Brahmacharileishmanoid.

He published about 150 research papers. Much of his research work has been collected in two volumes under the title, Gleanings from my research. The University of Calcutta published these in 1940 and 1941. He was a Fellow/Member of Asiatic Society (President, 1928-29), Indian Institute of Science, and Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science; Fellow/Patron of Indian Chemical Society, Society of Biological Chemists (India), Physiological Society of India, Royal Society of Medicine (London), and Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (London), and Honorary Fellow of State Medical Faculty of Bengal and the International Faculty of Science (London). He was elected Fellow of the Indian National Science Academy in 1930.

Brahmachari was showered with many awards and honours including the title of Rai Bahadur in 1911. He was the recipient of the Coates Medal and Griffth Memorial Prize of Calcutta University, Minto Medal of the School of Tropical Medicine & Hygiene, Kolkata (1921); Kaisar-e-Hind Gold Medal (1924); and Sir William Jones Medal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. He was knighted in 1934. Sir Upendranath Brahmachari was the first Indian to be nominated for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

He was charitable by nature and donated generously to various organisations and made provisions for several awards, scholarships and medals at the University of Calcutta. The journal Science and Culture owes much to his generous donation. He contributed generously when the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research was setting up the Central Glass and Ceramic Research Institute in Kolkata.

Dr. P.N. Brahmachari, a relative of Upendra Nath Brahmachari, wrote in his memoir, “From the early days of his education, Upendra Nath began to show his proficiency and began to lead in his class. A quality that was apparent from his very early days was his faculty of remarkable memory. He acquired a good and thorough knowledge of English and could speak like an educated Englishman.

“His keen power of observation, critically analysing mind with the vast background of knowledge he had already acquired and the vast experience he was gaining day after day, made him an excellent clinician and his name and fame as a reputed physician of high calibre spread out far and wide in no time.”

Perhaps Sir Upendranath should have reached greater heights, even in colonial India. Although associated with almost all the scientific and literary organisations in Kolkata such as Asiatic Society of Bengal, Indian Association for the Cultivation of Sciences, University of Calcutta, and Indian Museum Kolkata, he did not engage through networks or leverage his connections. He never left the shores of India. On the other hand, he focused on the city he called home and the regions adjoining it. It is marvellous to see his multi-faceted interests and achievements. No wonder he was considered the “Living dictionary of medicine” of his time. He was a pioneer of modern drug research in India through his work on urea stibamine the first of the modern drugs originating in India. The Dr. U.N. Brahmachari Street in Kolkata is the great person he was.